Increase in poverty in Kenya in the 1980s

In the early eighties, poverty increased at a rapid rate in Kenya.At the time of Independence in 1963, Kenya took on many loans which did not need to be paid back until after a period of up to twenty years. By the 1980s these loans, and the interest on them, had to be paid, and much of the country‘s foreign currency earnings was used to repay them.

An increase in the population, the lack of a corresponding increase in production, and the corruption of government officials and embezzlement of public assets and funds added to the problem.

Shortage of arable land in some areas caused many people to shift to more fertile and less populated areas, and caused many others without sufficient income from the land to come into the cities and towns in search of work.

Wars in neighbouring countries, tribal wars, insecurity, and the lack of a maintenance of infrastructure, led to investors fearing to invest too much and caused a drop in tourism, the country‘s chief foreign currency earner. Furthermore, recurrent drought and famine in Machakos, Kitui and north-eastern Kenya in the late seventies and early eighties brought thousands of people into Nairobi in order to survive.

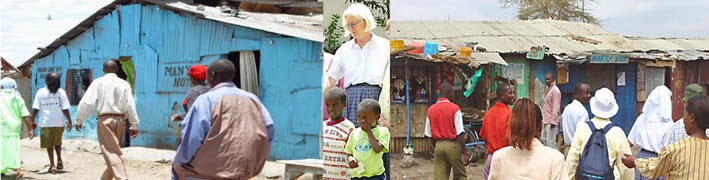

Growth of Shanty Town Slums

The result was the rapid and enormous growth of shanty-towns, or slums, as we call them in Nairobi.Along the Ngong River, which flows between the Industrial Area of Nairobi and South B, huge slums sprang up in the late seventies and early eighties. People running away from the wars in Uganda, Somalia, Rwanda, Sudan and within Kenya itself, people running away from hunger due to drought in Machakos and Kitui, and people running away after being evicted from the Mathari and Kibera slums to make way for high rise apartments, all came into the Industrial area and constructed temporary dwellings.

Some adapted quickly to city life, finding casual work and surviving quite well.

Most eked out a miserable existence by scavenging for all sorts of waste materials that could be sold. These ones barely made enough money to get shelter and food. Certainly there was no money left over for medical services or education.

School Fees exclude poor from education

Making matters harder, the Kenya government also introduced an extra year of primary education in 1985.As it did not have the resources to pay for the extra classrooms and workshops, parents were requested to share educational costs by building the necessary buildings.

In each school the parents committee, together with the head teacher, worked out the amount each parent would have to pay.

The children of those parents who could not pay were not allowed to continue in school. So, from a 90% attendance at primary school at government and formal private schools in the City of Nairobi in 1976, numbers have plummeted to 47% today.

Nowadays voluntary organisations such as the Mukuru Promotion Centre cater for a further 27%, while the remaining 26% of children loiter on the streets, begging, scavenging and engaging in petty crime. Most sniff glue in order to get "high" to forget for a time the pain of hunger and the misery of their existence.

Slum people demand educational facilities

Before Independence, many rural areas did not have schools so many ordinary slum dwellers had not gone to school when they were young. As a result, they very much wanted their children to be educated because they knew that that would mean their children could potentially earn a better living than they themselves had been able to.When they found that they could no longer get their children into school, they were very upset, and with the impossibility of school attendance came a terrible desperation and despair. Drunkenness and apathy increased, and as people lost hope for a better future for their children, they worked less and drank more.

Then some parents from the Mukuru slums organised themselves into a group of about fifty and began visiting government offices, churches, NGOs and religious congregations, pleading for help with the problem of basic education and basic health care.

We, the Sisters of Mercy, were among those approached. The matter was discussed in 1983, with most of the sisters of the opinion that the problem was for the government to work through rather than any one else. Yet, the problem was there, and the children who were out of school were getting worse daily: the longer they stayed out, the more they deteriorated.

Sr Mary Killeen and Fr Manuel Gordejuela set up Mukuru Promotion Centre

I felt very badly when I walked each day to my former school and met ragged,

half-starved children coming from the slums and going into city to beg,

scavenge, or even in some cases, steal. I felt strongly that something should be done, so I approached the Missionaries of Africa, the priests in our local parish, and found that one of them, a Spaniard called Fr. Manuel Gordejuela, was also very interested in the plight of the children.

The parents had spent many months following the District Officer to get a site for the school and in May 1985, Father Manuel and I started a small informal school in the Mukuru Kayaaba slum, calling the project the Mukuru Promotion Centre.

I was working part time in Mukuru from 1985 until 1989, as I was still head teacher of my former school. Then in 1990, the Sisters of Mercy and the City Council of Nairobi transferred me to Mukuru to work full time there.

To start with the school catered for children over ten years old that were loitering on the streets, and our aim was for the children to become literate and learn a trade so that they could be self-sufficient. Many of the children from this informal school did succeed and are now working.

Schooling and Social Problems

I found that the parents and their children had a huge desire to be seen as respectable Kenyans. They wanted to do the state examination and receive a certificate of primary education.The children attended school regularly and compared very favourably with the normal city children.

However, I soon came across some enormous problems.

There were thousands of children on the street and the longer they stayed out of school and on the streets, the more costly it became to educate them.

Hard-core street children could only be taught by expert teachers in small groups, whereas slum children who did not have street experience could be taught in groups of forty.

Although I continued to admit older street children to the school, I tried to admit most of the children before they went to the streets and in the meantime gradually set up back-up services to help with the well-being of all the children.

Mukuru Promotion-Centre Projects

First of all we employed some social workers to follow the cases of the children who were dropping out of school. Usually these children were the most needy, often of single mothers who were sick with AIDS and so the children had to work to get income.

There is no social welfare in Kenya and so the unemployed have no income and have to beg, scavenge or run a small business of buying and selling so that they can survive. If unemployed and sick, they depend upon the earning power of their children for their daily food.

The social workers try to ensure that this vulnerable group of children get a chance to stay in school by providing food for the families of dying Aids patients, and by enabling the single mothers to have a small business or receive training for employment.

They also organise the community so that it can solve some of its own problems, for instance, at present, different slum communities are busy replacing bridges swept away by the floods, and constructing latrines and drains to try to prevent outbreaks of disease.

We also badly needed basic health services, so we employed two nurses. These nurses look after the health of the children and of the destitute without income. They also train community health workers in preventative medicine.

This year we had outbreaks of cholera and typhoid due to the heavy rain and floods, but because of the health services we now have, we did not experience the large number of deaths we used to in the early days of the project. In addition, the nurses are busy training midwives, because, due to the increase of poverty, mothers can no longer afford to go to hospital to deliver.

In terms of further education, we try to get sponsors for those children who are very bright academically but who do not have the means to go any further. We have past pupils who now have university degrees, some who are at present in university, and others who have qualified to go but who do not have the means to continue. Hundreds of slum dwellers are now able to earn their living because of our intervention.

Apart from the five schools, with about 4,300 pupils in total, we also run a children‘s home with a capacity for 128 orphans.

Because some of the orphans are innocent children who have not had street experience and others are hard-core street children, we have had some bad experiences where a street child would run away taking innocent children with him or her. Some small street girls who engaged in prostitution were also pimps. Sent by their own pimps, they would pretend to want to go to school and would get admitted to the home, then after a few days they would return to the street taking a few innocent girls with them. We therefore run a shelter for hard-core street children so that we can try to rehabilitate them and find out more about them first before mixing them with the innocent and already-rehabilitated children.

Support of DKA and KFS

How have we managed to do this work?

Principally through the help of an Austrian NGO called Dreikonigsaction, a charity involving children.

At Christmas-time the children dress as the three Kings and go around their neighbourhood telling the Good News of Christ‘s birth and singing carols. Those who hear them give donations, which the children take to their organisation. Their donations are used to help other very poor children, such as the Mukuru children, to have the basic necessities of life.

Through the efforts of these Austrian children thousands of slum children are able to get a basic education, learn a trade and to keep themselves and help their families.

Then, when Mr Wolfgang Bohm of Dreikonigsaction came to visit and saw the difficulty we had in trying to raise funds whilst running the centre, he realised we desperately needed more secure funding to sustain the activities. He approached KFS to ask it to assist our work and support what Dreikonigsaction was doing. KFS agreed and suggested getting help from the Austrian Government and the EU.

The proposal for funding was originally requesting support for the years 1987 to 1989, but in fact still continues today. This support has given stability to our existing operations, and so we are very fortunate that these two Austrian-based NGOs supported our work for the poor. Without their help and encouragement, much of our work would still be a proposal and many children would be without an education or the skills to earn their living.

Other funds: ERKO, Austria, Trnava University, EU and miscellaneous sources

When Slovakia became independent, an organisation called ERKO was formed which aims to get the Slovakian youth to help develop themselves morally and spiritually, and help them to reach out to assist very poor children around the world. Dreikonigsaction put ERKO in touch with Mukuru Promotion Centre, and ERKO joined in supporting the work of the Mukuru Promotion Centre. Then through ERKO, the University of Trnava got involved by supporting the health section of the project, both with volunteers and medicines.

I find it wonderful that the efforts of the children of Austria and Slovakia actually give a better life to the children of the slums of Nairobi.

I am also very proud of the fact the Austrian Government and the EU stepped in to supplement what the children were doing.

Most EU-sponsored projects in Nairobi consist mainly of building very beautiful buildings for use in education. In the Mukuru project there are no big buildings: all five schools consist of shanty-huts, built like the people‘s houses. Instead, the bulk of the EU grant is spent on providing basic teaching and basic facilities so that the children can be developed and eventually be responsible adults.

I wish to express my gratitude and appreciation to Dreikonigsaction, KFS of Austria, the Austrian government, ERKO, Trnava University of Slovakia and the EU for the partnership we have shared, and for the wonderful results of our combined efforts. Together we have enabled thousands of desperately poor children in Nairobi to take their place in society. May such partnerships as this grow and flourish!

No comments:

Post a Comment